Who owns the mark? Prior user vs. the first-to-file registrant

30 November 2020

When two pharmaceutical trademarks with similar names hit markets in the Philippines – one of which is a user in good faith and the other a registrant in good faith – things can get sticky. Editha R. Hechanova takes us through the tale of how confusingly similar trademarks can co-exist in the same market.

In the landmark decision in the case of Zuneca Pharmaceuticals v. Natrapharm Inc., (G.R. No. 21850, September 8, 2020), the Supreme Court of the Philippines ruled that registration is the exclusive means of acquiring ownership of a trademark, overturning its earlier rulings in 2010 in the cases of Berris Agricultural v. Abyadang (G.R. 183404), and E.Y. Industrial Sales v. Shen Dar Electricity and Machinery (G.R. 184850), where it pronounced that “a trademark is a creation of use and belongs to one who first used it in trade or commerce.”

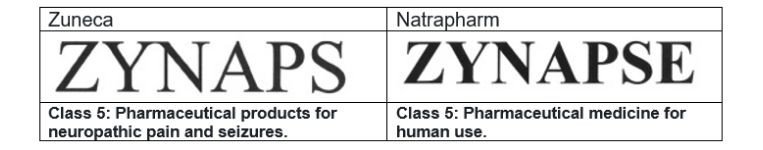

This case arose from a trademark infringement case filed by Natrapharm against Zuneca Pharmaceutical on November 29, 2007, before the regional trial court (lower court). A side-by-side comparison of the contending marks and the goods covered is shown below.

Both parties agree that their marks are confusingly similar, especially so when the goods bearing their marks are both pharmaceutical products. ZYNAPS is the brand name for a drug called carbamazepine, which is an anti-convulsant used to control all types of seizure disorders, such as epilepsy, among others. ZYNAPSE is the brand for a drug manufactured by Natrapharm called citicoline used for treating cerebrovascular disease or stroke.

Zuneca, which has not filed a trademark application for its ZYNAPS brand, claimed that it is a prior user in good faith and has been using the mark since 2004, and prayed for the cancellation of Natrapharm’s registration on the ground of bad faith considering that the latter was aware of the ZYNAPS mark before the ZYNAPSE’s trademark application for registration was filed and obtained. Zuneca alleged that both of them had advertised in the same publication and joined the same conventions to promote their products. In the case of Natrapharm, it filed its ZYNAPSE mark on June 1, 2007, and was registered on August 24, 2007, and also claimed good faith since it alleged lack of knowledge of the existence of ZYNAPS prior to the registration of ZYNAPSE. Further, it gave an account of how they came about the mark ZYNAPSE, which came from the neurological term “synapse” and the measures taken such as checking the Bureau of Food and Drug (now Food and Drug Administration), the Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines (IPOPHL) and other databases for the availability of the ZYNAPSE name. After trial of the case, the lower court ruled that the first filer in good faith defeats a first user in good faith which did not file any application for registration. Natrapharm, therefore, as the first registrant has all the trademark rights over ZYNAPSE and can prevent others, including Zuneca, from registering an identical or confusingly similar mark. It rendered judgment against Zuneca, finding it guilty of infringement and ordered it to pay Natrapharm damages amounting to P2.2 million (US$46,000). Further, Zuneca was enjoined from using ZYNAPS, and further ordered the destruction of all infringing materials, without compensation. Feeling aggrieved, Zuneca appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals, which affirmed the lower court’s decision, and ultimately appealed to the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of its dispute.

Proving bad faith

During the trial, Zuneca had the burden of proving that Natrapharm was in bad faith and obtained the ZYNAPS registration fraudulently. Citing the case of Mustang Bekleidungswerke GMBH v. Hung Chiu Ming (Appeal No. 14-06-20, Aug. 29, 2007, IPOPHL ODG), “bad faith means that the applicant or registrant had knowledge of prior creation, use and/or registration by another of an identical or similar mark.” The lower court found the evidence submitted by Zuneca insufficient, and held that the fact that ZYNAPS and Natrapharm’s other brands were listed in a common directory was not enough to show bad faith considering that Zuneca’s own witness admitted not having knowledge of the drugs listed in the said directory, and the same level of knowledge should be applied to Natrapharm, giving the latter the benefit of a doubt. Had the evidence of Zuneca been found sufficient, Natrapharm’s registration could have been cancelled since it would not be reflective of the ownership of the holder, as in the following instances: (i) the first registrant has acquired ownership of the mark thru registration but subsequently lost it due to non-use, (ii) the registration was done in bad faith, (iii) the mark itself became generic, or (iv) the mark was registered contrary to the provisions of the IP Code.

The Supreme Court ruling

Under Section 122 of RA 8293 (IP Code), the rights on a mark shall be acquired through registration made validly in accordance with its provisions. To remove any doubt on the intention of the lawmakers, the Supreme Court reviewed the deliberations of the lawmakers in crafting the IP Code, and quoted the sponsorship speech of the late Senator Raul Roco to show that in order to comply with the TRIPS agreement and other international commitments, the proposed law no longer requires prior use of the mark as a requirement for filing a trademark application, and abandoned the rule that ownership of a mark is acquired thru use by now requiring registration of the mark in the IPOPHL. Two justices dissented and could not agree that the present IP Code abandoned use as a mode of acquiring ownership since the IP Code mandated the filing of declarations of use. This was explained away by making the distinction that use is not a mode of acquiring trademark ownership, but use is required to maintain ownership of the registration.

The prior user in good faith

The IP Code under Section 159.1 provides that a registered mark shall have no effect against any person who in good faith before the filing or priority date was using the mark for the purposes of his business or enterprise. The Supreme Court ruled that Zuneca, being in good faith, is not liable for trademark infringement. Hence, the award for damages and the other penalties were removed. Section 159.1, however, limits the right of the prior user in good faith as regards transferring or assigning its trademark rights, by mandating that the business or that part of the business involving the mark should be transferred as well. The Supreme Court highlighted this provision by stating that the mark ZYNAPS cannot be transferred independently of the business or enterprise using it.

The implications of the decision

Co-existence of confusingly similar marks in the market. Since Natrapharm is a registrant in good faith, and Zuneca is a prior user in good faith protected by Section 159.1 of the IP Code, the ZYNAPS mark of Zuneca and ZYNAPSE mark of Natrapharm will co-exist, notwithstanding that they are confusingly similar, to the possible detriment of the consumers. The drugs are directed towards different ailments and have different composition, and the possibility of medical switching, whether deliberate or by inadvertence, can occur, resulting in injury to the patient. The Supreme Court believes that the occurrence of confusion to the public is mitigated by the fact that the Generics Act of 1988 as amended by the Cheaper Medicines Act requires the generic name of the drugs to be written in prescriptions, and physicians who fail to do so are subject to penalties. Recognizing, however, the possibility that medical switching could arise, the Supreme Court ordered the parties to indicate on their respective packaging, in plain language understandable by people without medical background or training, the medical conditions that each drug is supposed to treat, and a warning what each drug is not supposed to treat, and to show to the court compliance with said directive within 30 days. Whether this will actually work or not remains to be seen, and because the marks are nearly identical in appearance and sound, the likelihood of confusion remains a high possibility.

Need to make trademark owners more aware of their IP rights. This landmark decision clearly underscores the necessity for trademark owners to file and obtain registration for their trademark. The Philippine economy is driven by SMEs and MSMEs, which comprise about 99.6% of the total number of enterprises in the country. The potential prior users would most likely come from this sector, particularly since intellectual property is not usually top of their mind. While some degree of awareness has been noted as evidenced by the increasing number of filings coming from domestic entities, many of these businesses do not regard protecting their IP rights as important as getting their goods or services sold and accepted by the consumers. Only when others start copying them do they become aware of its importance. From a limited survey of SMEs that we conducted earlier this year, the lack of interest stems mostly from the lack of awareness of IP, and the attendant cost and access to the IPOPHL for the registration. While the access has been made easier by the IPOPHL in the sense that online filing is encouraged, the challenge to the SMEs is connectivity and investment in computers.

Review of IP Code to recognize the rights of prior users who have no registered marks. Building awareness of IP rights take time and must be coupled with some form of incentives for SMEs to seriously think of. The current IP Code is being revised, and the dissenting opinions of Justices Leonen and Lazaro-Javier would be instructive in crafting clearer provisions that could be more practical and fair to the SMEs that would allow for the recognition of prior use in good faith as a mode of acquiring ownership of a trademark.

The current Section 159.1 limits the commercial exploitation of the prior user in the sense that the business has to be assigned or transferred with the mark. Why can’t the mark be sold without selling the business?

Review of FDA Rules. By agreement between the IPOPHL and FDA, the latter left to the IPOPHL the matter of confusing similarity of trademarks. In the past, the FDA checked their own records and did not allow a similar name of the drug to be registered. Since the FDA is the first agency that would be approached by a manufacturer or drug trader to obtain product registration which is required before the drug is sold or offered for sale in the market, the authority to check not only the technical specification of a drug, but also its name as well should be part of its function.