The interplay between Indian design and trademark law: Peaceful in 2D, complicated in 3D?

31 March 2020

Lines between trademark and design law are blurry when one is considering the protection of the shape and the three-dimensional layout of a particular product. Pravin Anand, Vaishali Mittal and Siddhant Chamola explain how the laws intersect.

Lines between trademark and design law are blurry when one is considering the protection of the shape and the three-dimensional layout of a particular product. Pravin Anand, Vaishali Mittal and Siddhant Chamola explain how the laws intersect.

Students and practitioners of intellectual property law across different jurisdictions are very often in situations where they realize that a singular subject matter may be protected by two or more regimes under IP law. For instance, a new piece of software can be patented as well as protected by copyright as a literary work; a creative banner can be protected as a trademark as well as under copyright as an artistic work. While some of these common fields of operation are fairly simple for newbies, some overlapping fields lie on the other end of the spectrum.

One such example of the latter is the relationship between the statutory regimes of design law and trademark law. Things start to become a little nuanced where the protection of the appearance of a three-dimensional product (or article in the case of design law) is concerned.

Scope of protection under the Designs Act, 2000 and the Trade Marks Act, 1999

The Designs Act, 2000. A design registration confers exclusive rights over only features of shape, configuration, pattern, ornament or composition of lines or colours, when applied to articles in two-dimensional and/or three-dimensional forms. The protection granted to a design is with respect to its appeal, when it is solely judged by the eye.

Further, the Designs Act, 2000 excludes inter alia the following from the very definition of a design:

-

That which is a trademark; and

-

Anything which is a mere mechanical device.

In simple words, a design registration protects two-dimensional or three-dimensional aesthetic features of a particular article, which are visible to the human eye.

In order to proceed to registration, a design must be novel and original; it must not be prior published and must satisfy other fundamental criteria especially laid down in the Designs Act, 2000.

In the landmark decision in Microfibres Inc v. Girdhar & Co. & Anr., the High Court of Delhi held that the legislative intent behind the Designs Act, 2000 was directed towards providing a limited monopoly of 15 years (extendable by a further period of five years) to design activities which were commercial in nature. The court further held that the Designs Act, 2000 was enacted to fuel industrial inventiveness in the field of commerce.

The Trade Marks Act, 1999. In contrast, the Trade Marks Act, 1999 states that a “mark” includes a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colours. Furthermore, a trademark is defined as a “mark” which is capable of being represented graphically and which distinguishes the goods and services of its proprietor from those of others.

In order to secure registration for the shape of a product, its proprietor must demonstrate (amongst other criteria) that the shape is not necessary to obtain a technical result.

This legislation replaced the erstwhile Trade & Merchandise Marks Act, 1958. The “Statement of Objects and Reasons” of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 – which explains the need behind the Parliament to introduce a new regime – clearly states that the new legislation was enacted to meet the developments in trading and commercial practices in an increasingly globalized world. As a result, India recognized new concepts of “well-known” trademarks as well as unconventional trademarks covering colour-combinations and (amongst others) the shape of goods as well.

Unlike a design registration, there is no limitation placed upon the term for which a trademark may be registered, since the Trade Marks Act, 1999 entitles a registered proprietor to continuously renew its registration. Theoretically, a registration may be renewed in perpetuity as well.

Are designs and trademarks mutually exclusive?

While there are several inferences and analyses that one may arrive at, one thing becomes quite clear: the shape of a particular product may be registered as a design, as well as a trademark.

This begs the question whether these aspects of a product can be protected under both regimes simultaneously. If not, does an attempt to secure simultaneous protection result in disqualification from seeking registration under both regimes? A short response to these questions is NO!

These questions have not been answered comprehensively in any singular case in India. Instead, the answer and its reasons need to be distilled from principles of law which have evolved from one case to the other, and from a careful analysis of the two statutes.

Two dimensional aspects. While a design clearly excludes a trademark from its ambit, there is no such exclusion for a design under the Trade Marks Act, 1999. Strictly speaking, the shape of a product is always three-dimensional.

As far as the relationship between design and trademark law in India is concerned, the two regimes operate without any disturbance. This is also because aspects of pattern, line or colour composition which has been used as a trademark, cannot be registered as a design by virtue of the statutory bar residing in Section 2(d) of the Designs Act, 2000.

Three-dimensional aspects. It is in the 3D realm that things become slightly complex and the fine lines between a design and trademark begin to blur. Since a three-dimensional shape can be protected under both regimes, there are several issues with which a proprietor is routinely confronted:

-

Phase 1 – Whether the article should be protected as a design, or as a trademark.

-

Phase 2 – If protected as a design, can one assert trademark rights and common law rights of passing off over the shape of the product?

-

Similarly, if protected as a trademark, can one seek registration of the shape as a design?

-

Phase 3 – Upon expiration or cancelation of the design registration, can one enforce rights and common law remedies of passing off on the product as a trademark?

-

Similarly, upon expiration or cancellation of the trademark registration, can one seek registration and enforce rights on the shape as a design?

Design or trademark: A choice dictated by circumstances

The answer to each of the above questions, which often perplex artists and business houses, resides as much in statutory bars under the Designs Act, 2000, and the Trade Marks Act, 1999, as it resides in the circumstances and facts that precede the questions themselves.

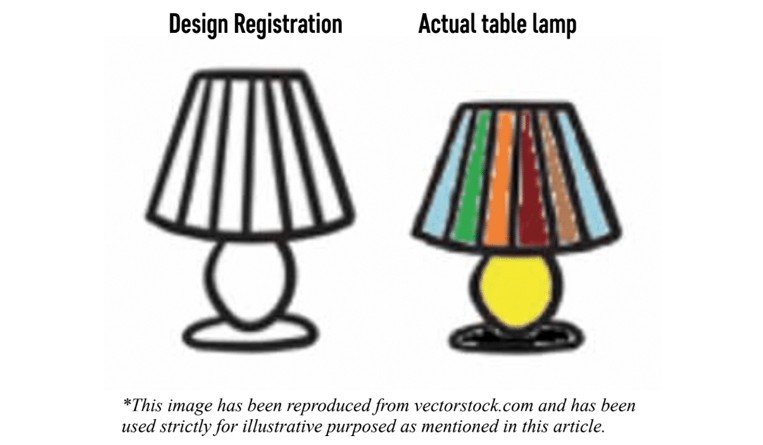

Phase 1 – Starting out! Let’s consider a quick hypothetical. F, a reputed designer, comes up with the concept for a new, stylish table lamp. The design is not promoted anywhere and the table lamp is not put to production. Fearing mass production of cheap imitations, F has decided to get a “shape mark” registration over the table lamp, so that it can protect the appeal and visual identity of its table lamp.

However, T, F’s sister-concern in the interior decor industry, tells F that its lawyers advised it to register all its table lamp as “designs” instead.

In this situation, F will be on stronger footing to secure a design registration over its table lamp, for the following reasons:

-

The design for the table lamp is new, novel and not prior published;

-

The table lamp has not been used or claimed by F to be a trademark; and

-

A registration will confer F with an exclusive right to restrain third parties from making imitations of its table lamp, for a period of 15 years.

Therefore, for the next 15-20 years, F’s commercial interests will be protected and its creative efforts will also be protected by the force of law. This fulfils F’s aim of preventing imitations of its table lamp in the market.

On the other hand, had F sought registration for its table lamp as a shape mark, then it would have had to meet a very tall and strict test under Section 9 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, i.e., to demonstrate that the shape, colour combination etc. of its table lamp is distinctive and sets its product apart from those of others. Though this may not be an impossible feat, it certainly is a tough one especially for a product which has not been introduced in the market.

Phase 2 – The reigning registrant! Five years have passed and F’s table lamp has become very popular for its unique aesthetics, so much so that traders have started making imitations of it, and have started selling them at much cheaper rates.

F wants to file a lawsuit against one such trader, and approaches its IP lawyers for advice. F is informed that its design registration protects the aesthetics and shape of the table lamp only, and it does not extend to the unique stripes, the fanciful fusion of colours that the table lamp is also famous for.

F is also advised that it cannot claim the common law remedy of passing off over the entire visual appeal (including shape, colour combination, placement of trademark and symbols etc.) a trade-dress or as a three-dimensional trademark. If it does so, then it risks the invalidation of its design.

So what options does F have?

The recent decision of the Delhi High Court, in a bench comprising five judges, in the decision of Carlsberg Breweries v. Som Distilleries has put this controversy to rest in clear terms. The court has stated that a single suit can invoke claims of piracy of design as well a claim for passing off. In doing so, the plaintiff must ensure that the elements of design are not used as a trademark, or as a larger trade dress, get-up, and presentation of the product.

Therefore, in this situation, F can file a suit against the trader, seeking an injunction against its table lamp shape as well as colour combination, placement of insignias etc., with the following claims:

-

A claim for piracy of design on the shape and aesthetics of the table lamp; and

-

A claim for passing off with respect to the colour combination, placement of insignias etc.

Phase 3 – Second Innings? Twenty years have passed since F’s design registration, and its table lamp has attained iconic status. Its shape and trade-dress has become an automatic source indicator for F’s décor-house. In fact, it is so iconic that counterfeiters and imitators are still making infringing versions and reaping off F’s goodwill.

However, they have become smarter over the years and have used different colour combinations and insignias, knowing very well that it is the shape and aesthetics (devoid of colour) of the table lamp which is more iconic and gets customer purchases.

F is disappointed, thinking that it has no options anymore since the design registration over the shape of the table lamp, has lived its life. F recalls its lawyers’ advice a few decades back that a design can never be pressed as a trademark.

So, in this final situation, does F really have no option? Much to F’s surprise, it can claim trademark and trade-dress rights on the shape and aesthetics of as well as on other elements of the table lamp!

Until quite recently, it was a commonly held view that a design, once registered, cannot be pressed as a trademark, and that one cannot engage in “backdoor evergreening.” In other words, once a monopoly over the shape of an article, conferred through a design registration, expires, then no further statutory or common law rights can be pressed on it as a trademark. This view was also supported by judicial precedent of the Delhi High Court in cases such as Crocs Inc USA v. Bata India and a host of connected cases initiated by Crocs Inc.

However, this Single Judge’s judgment was overturned on appeal, by the Division Bench of the Delhi High Court.

A recent judgment of the High Court of Calcutta addresses this conundrum quite well, and it emphatically states that a design, once expired, can certainly be protected as a trademark, if it enjoys goodwill and the consuming public associates the product with its proprietor. In Super Smelters Limited v SRMB Srijan Private Limited, the court established two succinct principles:

-

That rather than granting monopolies to the shape of an article, the law of passing off merely recognizes the existence of a monopoly over that shape that is held by the proprietor; and,

-

A registered design, after its expiry, may not lose its distinctiveness and end up fulfilling all the requirements of a trademark. In that scenario, not recognizing that mark as a trademark because that would extend the design monopoly would be to conflate two things that exist completely independent of each other.

Conclusion

As stated earlier, the conflict between design and trademark law is non-existent in situations involving two-dimensional aspects and features of a particular product.

Lines between trademark and design law seem to be a little blurry when one is considering the protection of the shape and three-dimensional layout of a particular product. Based on the analysis presented in this article, a few rules or principles which can be crystallised are as follows:

-

Simply put, the shape and aesthetics of a product can be protected by design registration. Other features which are not claimed in the design registration (such as larger trade-dress, layout, placement of trademarks on the product etc) can be protected under a trademark or trade-dress.

-

However, during the pendency of the design registration, if the proprietor applies for the entire design as a trademark; or claims that the entire design is also a trademark / trade-dress, and ensures that the consuming public associates the entire design as a source indicator, then the design registration will become susceptible to cancellation.

-

It must be remembered that while the very definition of a design excludes a trademark, a trademark does not exclude a design! Therefore, even if one does claim design as well as trademark rights on exactly the same features of a product, then design rights may extinguish. However, trademark and related common law rights will continue to subsist.

-

Once the design registration expires, then the entire design can be claimed as a trademark/trade dress and appropriate legal action can be initiated by its proprietor, provided the test of consumer association and goodwill is satisfied. This is because common law does not confer monopoly on a product. Instead, it merely recognizes and protects the monopoly which already exists on the shape and aesthetics of a particular product.

-preview.jpg)