When Mickey Mouse enters the public domain

29 February 2024

As Mickey Mouse joins the public domain, questions arise about the implications for derivative works and the balance between IP protection and fostering creativity. Excel V. Dyquiangco checks in with legal experts.

The recent entry of Steamboat Willie, the earliest version of Mickey Mouse, into the public domain in the United States has ignited discussions on the implications for Disney’s extensive character portfolio and the potential for new creative interpretations.

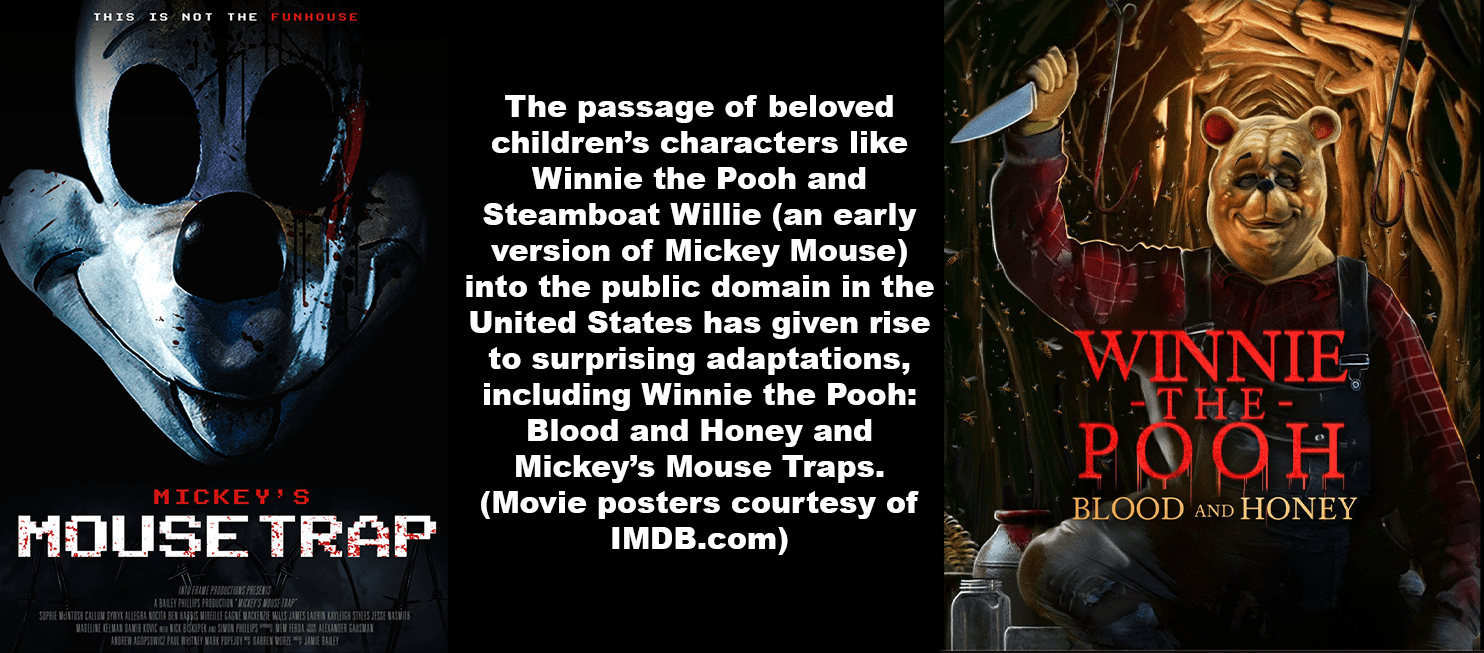

Steamboat Willie’s newfound freedom parallels the journey of Winnie the Pooh, whose public domain status led to surprising adaptations such as Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey. Now, Mickey Mouse is in a similar position, facing legal entanglements as creators explore fresh and unexpected contexts, such as the upcoming horror film Mickey’s Mouse Traps.

The move raises questions about the implications for Disney’s extensive character portfolio and the potential for a more lenient stance on derivative works. It has sparked a broader conversation about the balance between protecting IP and fostering creative reinterpretations in the digital era.

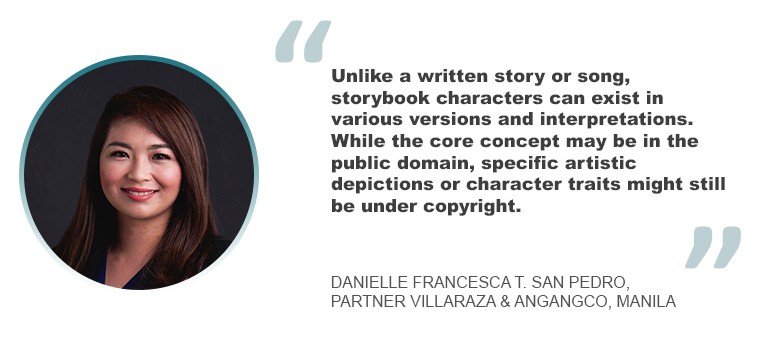

usually happens when copyrighted work goes into the public domain. “A unique aspect of storybook characters that may not apply to other creative works is that, unlike a written story or song, characters can exist in various versions and interpretations,” she said. “While the core concept may be in the public domain, specific artistic depictions or character traits might still be under copyright.”

Further, she added that characters can gain further protection through other types of IP rights. For instance, registering a unique appearance or portrayal of a character, along with their names, as trademarks. Even if the original literary or artistic work containing the characters is already in the public domain, certain aspects of the character can still be safeguarded under specific conditions.

Mudit Kaushik, a partner at Verum Legal in New Delhi, emphasized that only the 1928 iteration of Mickey Mouse has entered the public domain. Subsequent developments of the character remain under Disney’s copyright protection, including distinctive features such as Mickey’s rounded ears and personality traits. “While artistic reinvention of Steamboat Willie is permissible, commercial exploitation of later versions of Mickey without Disney’s express permission remains prohibited,” he said.

He added: “Disney possesses a robust portfolio of trademarks encompassing the name and various visual representations of Mickey Mouse. These trademarks safeguard the character’s distinct identity and ensure an unwavering association with the Disney brand. Therefore, while artistic reinterpretation of Steamboat Willie is permissible, exploiting later versions of Mickey on merchandise or in works potentially leading to consumer confusion with Disney is expressly forbidden. This trademark protection extends beyond mere appearance, encompassing even the characteristic gestures and personality traits that have cemented Mickey’s status as a cherished cultural icon.”

Interestingly neither Winnie the Pooh or Steamboat Willie were the firsts. When Disney Studios produced their animated film The Little Mermaid in 1989, the original Little Mermaid story, also known as Den lille havfrue, penned by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, had already entered the public domain. The tragic narrative was significantly altered in Disney's rendition, which included giving the main character, Ariel, a new name, as well as adding memorable supporting characters like Sebastian and Flounder and even rewriting the story’s conclusion. Even with this change, Disney still has the copyright on its own adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, which includes Ariel’s name and appearance.

This pattern extends to other Disney classics, including the 1967 adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894), the 2013 adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen (1844) and the 1992 adaptation of Aladdin from the collection of Middle Eastern folktales compiled in One Thousand and One Nights.

Meeting certain conditions

Even with copyrighted works entering the public domain, not all can be rehashed into other mediums. “Characters from stories or books can indeed be eligible for copyright protection, but certain criteria must be met to enjoy this safeguard,” said Kaushik. “These criteria pertain to the uniqueness and non-generic nature of the characters.”

Kaushik said that characters can be categorized into two main types: graphic characters and fictional characters. “These distinctions are crucial because courts have established different tests for copyright protection for each category.”

Graphic characters are those that can be visually depicted, typically through cartoons or other graphic representations. Their physical appearance and characterization are readily apparent to readers or viewers. On the other hand, fictional characters exist as word portraits, with their physical attributes and personality traits residing in the minds of readers. The imagination of these characters is crafted through the pages of a book rather than through a single paragraph or line. Consequently, fictional characters are not immediately apparent to the reader.

“Given that images are more easily identifiable than literary descriptions, pictorial or graphic characters tend to be more straightforward to protect under copyright law, even when divorced from their original context,” Kaushik said. “However, it’s important to note that copyright protection for a graphic character does not extend to the character as a whole. Instead, copyright law can only protect the specific visual representation of the character. The character’s personality and traits, which are integral to its identity, do not fall under the purview of copyright protection as an ‘artistic work’. This is because these aspects of a character are not visually expressed but are rather aspects that can only be perceived by the human mind.

Moreover, the application of IP law can vary across countries. Pertaining to Kaushik’s discussion of fictitious characters, he notes that while Indian copyright law protects original literary, artistic, dramatic and musical works, including films and sound recordings, there is no explicit legislation in India addressing the protection of fictitious characters.

So, when storybook characters become part of the public domain, what are the consequences for derivative works or adaptations, and how does this influence the capacity of others to generate new content featuring these characters?

Kaushik said: “The public domain liberates creativity. When the copyright on storybook characters expires, creators are granted unparalleled artistic freedom. They can reimagine characters’ appearances, personalities and narratives without the need for permissions or adherence to copyright restrictions. This fosters a climate of unfettered creativity, enabling bold interpretations, experimental storytelling, and even subversive takes on beloved characters. It democratizes storytelling, allowing anyone with a creative spark to contribute, diversifying perspectives, and enriching our cultural tapestry. The public domain also stimulates commercial exploration. Characters become free for commercial use, opening doors for merchandise, spin-off stories and various ventures. This expansion of economic possibilities around these characters incentivizes further creative engagement and contributes to a vibrant ecosystem of content.”

Since the public domain applies only to specific iterations of characters in their copyrighted forms, later evolutions may still be under copyright protection. Trademarks associated with characters’ names or logos can also impose restrictions on commercial use.

Derivative works versus copyrighted works

To explain better this derivative work, San Pedro said that derivative works refer to copyrighted works that come from another copyrighted work. “The author has either obtained the appropriate consent of the author or copyright owner of the original work, or the original work is in the public domain,” she explained. “To be protected as a derivative work, the new work must contain sufficient original creative content to be distinguishable from the original work while still recognizably connected to it. Slight modifications or updates will not suffice.”

Under the IP Code of the Philippines, derivative works are treated as new works, deserving of their own copyright protection. This means that while the original work retains its copyright status, the derivative work is also safeguarded under copyright law. “That said, the derivative work’s protection is not lost when the original or parent work enters the public domain. Others may use the original work, but they cannot use the modifications or new elements introduced by the derivative work,” she said.

Furthermore, San Pedro highlighted the importance of the public domain in fostering creativity. Once a literary piece enters the public domain, its characters and elements become “freely and unconditionally used by third parties as-is, or in other forms, versions, and variations as in the case of new storylines, artworks, movies, and cartoons.” However, she noted that these derivative works must exhibit sufficient originality to qualify for copyright protection, ensuring that creators are rewarded for their innovative contributions.

“Contrary to what copyright owners may think, the copyright system and the public domain are two necessary sides of the same coin,” she said. “While the public domain fosters creativity and innovation, the copyright system protects and incentivizes them. Otherwise, allowing a system of perpetual copyright protection would result in a monopolistic and stagnant environment where audiences have no other options but to watch uninspired live-action movie adaptations.”

Permissible in other jurisdictions?

With Steamboat Willie entering the public domain in the United States, is his use also permissible in other jurisdictions? Not necessarily so, said Meryl Koh, a director at Drew & Napier in Singapore.

“If a business is keen to use Steamboat Willie for activities in a particular jurisdiction, it would be prudent to seek legal advice on whether Steamboat Willie is still subject to copyright protection in that jurisdiction,” she said. “This is especially so since each case will have to be decided on its own facts.”

Concerning copyright, Koh highlighted that each case must be evaluated individually, considering factors such as the origin of the expression and intended usage if the business intends to make changes to the expression. “From the perspective of Singapore law, legal counsel can then assess issues including whether the whole or a substantial part of that expression has been used such that the business may be found liable for copyright infringement and whether the business can rely on defences (fair use),” she said.

Meanwhile, concerning trademark or passing off, Koh underscored the necessity of conducting trademark searches to ascertain whether an expression has been registered. She advised businesses to be clear about their intended use and goods or services associated with the expression to assess the likelihood of consumer confusion and potential trademark infringement.

Regarding international treaties, such as the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works and the TRIPS Agreement, Koh explained that businesses from signatory countries receive automatic protection in Singapore. However, she advised caution and recommends consulting local legal counsel to ensure compliance with international copyright treaties and local registration requirements.

In Singapore, trademark registration is not mandatory, but it grants a 10-year statutory monopoly over a trademark in the country, enabling access to rights and remedies under the Trade Marks Act. “Without registration, businesses are limited to the common law action of passing off. If businesses are interested in registering their trademarks, it would be a useful rule of thumb for businesses to market and use their trademarks regularly,” said Koh, as this can deter others from registering similar marks. Local laws and counsel guidance are essential due to differing registration regimes.

Aside from the conventional practices above, businesses should also explore options and implement measures which keep pace with the rapid development of technology and the changing landscape of digital content creation, distribution, and consumption. First, with the advent of technology comes emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning. “Businesses may look towards patent law or the law of confidence (in particular, trade secrecy) to protect innovations in these areas,” said Koh. “Businesses may also wish to consult with local subject matter experts to ensure that they are not infringing upon the rights of others when developing such technologies – for example, a legal expert in Singapore could advise a business on the scope of Section 244 of the Copyright Act 2021, which provides that computational data analysis may be an exception to copyright infringement.”

Aside from copyright and trademark laws, businesses can consider implementing technological or confidentiality measures to minimize the risk of unauthorized use of valuable materials and information.

“For example, businesses can adopt technical protection measures such as encryption, authentication systems, or digital rights management,” she said. “They can also ensure that employees or key personnel have executed confidentiality agreements or non-disclosure agreements, and consumers have agreed to certain terms of use or terms of service. If, despite such measures, businesses find that third parties have unlawfully exploited their materials and information, they may consider an action for breach of confidence and/or breach of contract.”