Traversing SEP contours through the Indian Perspective: Ericsson v. Lava

31 July 2024

In a massive victory for Ericsson, the Delhi High Court, in its first final ruling in telecom SEP infringement, awarded US$30 million damages to Ericsson against Lava. Manisha Singh and Manish Aryan explain that, perhaps even more importantly, the court has finally settled the law regarding the determination of SEP, infringement of SEP, FRAND rate and calculation of damages, which will benefit other SEP cases pending in India.

Rights in standard essential patents (SEPs) are different than rights in non-SEPs, at least with respect to the rate of licensing the SEPs. SEP owners are bound by their commitment to the standard-setting organization (SSO) to make the patents available to those willing to take a license on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. However, courts across the globe, including India, have found it difficult to determine what the FRAND terms could be.

India, a huge market for telecommunication equipment with immense growth potential, has witnessed a series of legal battles between smartphone manufacturers involving telecom-related SEPs. In the last decades, Indian courts have delivered strong judgments related to SEP enforcement. Unlike other jurisdictions, Indian courts are open to issuing preliminary injunctions against unwilling licensees/implementors or directing them to deposit a part of their sales with the court or pay the plaintiff, depending upon the facts and circumstances of the case.

Between 2018 and 2022, some SEP implementers started to think that India’s stance had shifted, and interim relief was no longer available in SEP disputes. The Delhi High Court emphatically rejected this line of thought in March 2023 by upholding an interim order in Ericsson’s favour against the Indian mobile manufacturer Intex, which was refusing to take a license for Ericsson’s SEPs, and this way, introduced the concept of pro-tem deposit to secure an interest of SEP owners. After Intex v. Ericsson, a pro-tem security deposit was ordered in Nokia v. Oppo followed by Atlas v. TP-Link. Recently, on March 28, 2024, in a massive victory for Ericsson, the Delhi High Court, in its first final ruling in telecom SEP infringement, awarded Rs2.44 billion (US$30 million) damages to Ericsson against Lava.

The FRAND royalty rate which has been decided by the court applicable to Lava has been determined to be 1.05% of the net selling price of the devices sold by Lava. The decision in Lava has settled the law regarding the determination of SEP, infringement of SEP, FRAND rate and calculation of damages, which will benefit other SEP cases pending in India.

Brief facts

The dispute between the parties dates back to November 1, 2011, when Ericsson first approached Lava to get a license for its SEPs for the 2G and 3G portfolios. When the licensing negotiations failed, Lava filed a suit before the Noida District Court (the Noida suit) to seek declarations that Ericsson had waived its rights to enforce its claimed Indian SEPs by not asserting the same against the chipset manufacturers and to seek protection against Ericsson’s alleged groundless threats of litigation.

Ericsson responded by filing a suit for infringement of its eight SEPs and seeking permanent injunction and consequential reliefs, along with a declaration that the rates offered by Ericsson for its SEP portfolio were FRAND compliant. Lava, in its defence, filed a counterclaim seeking revocation against Ericsson’s eight SEPs. In the meantime, vide an order dated July 31, 2015, the Supreme Court transferred the Noida Suit to the Delhi High Court to be clubbed with Ericsson’s suit.

During the proceeding, the Delhi High Court passed a conditional interim injunction against Lava to deposit Rs500 million (US$5.98 million) with the court, which was reduced to Rs300 million in an appeal. Thereafter, a trial commenced in February 2016 and concluded in July 2016. Only after seven years of the trial the final hearing started in the matter in February 2023 and concluded on May 30, 2023, followed by the filing of their respective written submission.

Primary findings

Essentiality of suit patents and infringement thereof

The issue before the court was whether suit patents qualify to be standard essential patents (SEPs) in terms of the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) IPR Policy. The ETSI IPR Policy defines the term “essential” as follows:

“ESSENTIAL” as applied to IPR means that it is not possible on technical (but not commercial) grounds, taking into account normal technical practice and state of the art generally available at the time of standardisation, to make, sell, lease, otherwise dispose of, repair, use or operate EQUIPMENT or METHODS which comply with a STANDARD without infringing that IPR.

In other words, the term “essential” means that a patent is essential to a standard, i.e. it is not technically possible to comply with the standard without infringing it. Consequently, a standard essential patent is “a patent claiming technology that is essential to an industry standard’s use.”

To conclude whether the suit patents are essential to the ETSI standard, the court investigated the claim chart provided by Ericsson, which showed that the claimed features were also present in the technical standard of that technology. Additionally, the court considered Lava’s conduct and admission to conclude that the suit patents are essential. The court held that from the correspondence exchanged between the parties, it can be concluded that Lava was well aware of the essentiality of Ericsson’s patents and accordingly sought a FRAND license.

Most importantly, it was Lava’s admission in the written statement and counterclaim that went against them. In Paragraph 7 of their written statement, Lava specifically admitted that Ericsson’s claim mapping charts “provide one possible means to meet the standards.” However, Lava failed to prove the above statement with any cogent evidence, and thus, the essentiality of the suit patent was decided in favour of Ericsson.

Doctrine of exhaustion

Once the essentiality of the suit patents was decided, the court decided the defence taken by Lava that they have merely imported mobile handsets into India from licensed entities and, therefore, they cannot be held guilty of infringement of Ericsson’s patents. According to the principle of doctrine of exhaustion, the patent holder’s rights get exhausted after the first sale of the patented product by it or by its authorized seller. The law on the defence of exhaustion has already been decided in the case of Strix Limited v. Maharaja Appliances Limited, which requires the claimant to provide clear and cogent evidence that the imported product has been purchased from the licensee of the patent holder or by the authorization of the patent holder.

Lava failed to establish that the chipset suppliers or component manufacturers have a license from Ericsson. Lava did not enter into any agreements with chipset suppliers or component manufacturers, nor do they have any indemnification from them. So, the one learning implementors can draw from this case is that they should always do due diligence before purchasing any equipment covered by SEP and must enter into an agreement with an indemnification clause in case the SEP owners sue them in future. The whole defence of Lava on the doctrine of exhaustion was based on assumption without any due diligence.

Case of infringement

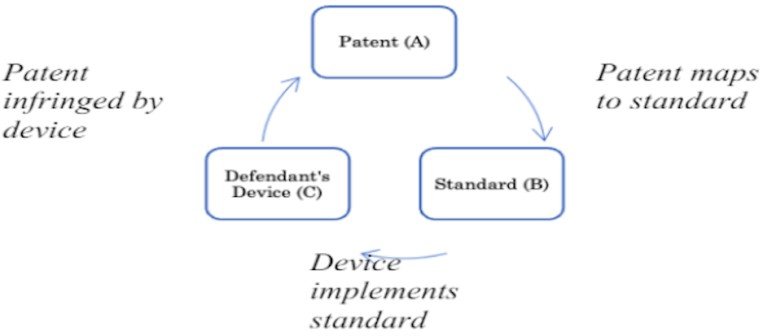

On the issue of infringement, the court relied on the High Court of Delhi Rules Governing Patent Suits, 2022, which gives useful guidance to courts in SEP litigation proceedings. The court also relied on the U.S. Court of Appeals decision in Fujitsu Ltd. v. Netgear Inc., which was approved by the Delhi High Court’s division bench in Ericsson v. Intex. The court followed the simple two-step test to determine infringement.

-

Mapping the patentee’s patent to the standard to show that the patent is a standard essential patent.

-

the implementer’s device also maps to the standard.

The following diagram best illustrates the two-step test for infringement. This is akin to the law of transitivity in mathematics, i.e., if A=B and B=C, then A=C, where A=patent, B=standard and C=defendant’s device. The Zeroth law of thermodynamics also says so.

Applying the two-step test, the court held that the devices of Lava are compliant with the ETSI standards as also optional standards, amounting to infringement of the portfolio of SEPs of Ericsson by Lava.

FRAND determination

SEP owners voluntarily commit to standard-setting organizations to provide access to the standardized technologies covered by the SEPs on FRAND terms to the willing licensees. There is always an inherent challenge in determining FRAND, as the determination should balance the equities between SEP owners and willing licensees. The court relied on the UK Supreme Court decision in Unwired Planet International Ltd. v. Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd & Others. The court held that India has one of the largest telecom industries in the world, and therefore, the global practices/principles of the telecom industry that are judicially recognized would have a bearing on the practices followed in the Indian telecom industry.

The court perused the correspondences between parties and found that Lava did not engage in negotiations with Ericsson in good faith, and therefore, the court declared Lava as an unwilling licensee. For the calculation of FRAND rates, the court held that comparable licenses had been negotiated between parties in similar circumstances, making the comparable licensing agreements highly reliable for determining royalties for a prospective licensee. The court rejected the top-down approach as suggested by Lava for the calculation of the FRAND rate.

Upon review, Ericsson placed 54 licenses on record, which the court held were comparable in nature as these agreements were made with entities similarly placed to Lava and were competing with Lava in the Indian mobile handset market. The court further held that the rates offered to Lava were consistent with those accepted by other similarly situated entities. Thus, the rates offered by Ericsson would fall within the FRAND range.

Quantum of damages

The court held that damages should be calculated based on the loss of royalty/license fee, and the damages should be granted for all devices, not just the tested devices. It is interesting to note that for the calculation of royalty, the basis should be the selling price of the end product and not the chipset. The court reasoned that the international jurisprudence on this aspect is unanimous and that the basis for calculating royalty should be the end product, not the chipset.

The court further held that damages should be granted for the entire portfolio, not just suit patents. In this regard, Lava argued that damages can only be granted for asserted patents and not the entire portfolio. The court held that Lava’s argument for licensing individual patents from a portfolio is not a workable proposition as this could cause substantial administrative burdens and inefficiencies for both licensors and implementers. Individual patent licensing is likely to increase transaction costs, legal complexities, and uncertainties in technology implementation. Consequently, the damages would have to be assessed based on the entire portfolio of patents and not just the asserted suit patents.

Calculation of Damages

For the calculation of damages, the court held that the most appropriate FRAND rate to apply in the present case would be the rate offered by Ericsson to Lava in November 2015, comparable to the rates negotiated by Ericsson with other similarly placed entities in India. The court penalized Lava for not negotiating the license in good faith by considering the upper range of the FRAND rate offered by Ericsson. For the calculation of damages, the court considered November 1, 2011, as the starting date of infringement when Ericsson approached Lava and May 8, 2020, as the cut-off date when the last of the asserted patent expired. The court calculated the proportionate sale figures of Lava’s device based on the figures provided by Lava and applied a 1.05% royalty rate per device, and held that Lava would be liable to pay damages to the tune of Rs.2,440,763,990 (US$30 million).

Conclusion

By this decision, the court upheld the internationally recognized principles for assessing the essentiality of patents in SEP litigation, gave weightage to comparable licenses for the determination of FRAND rate and rejected the top-down approach. The decision gives enough insight and strategy for defendants/implementors to succeed in SEP litigation. The first thing the implementors should remember is to enter negotiations in good faith and avoid holding out. Secondly, if infringement is denied, they should prove the existence of alternate technology to implement the standard. Although it took a very long time to decide on this SEP litigation after trial, it will guide other SEP litigations to decide more efficiently and judiciously.

About the authors

Manisha Singh, a partner at LexOrbis in Delhi, is a seasoned IP professional holding a decorated career spanning over two decades and repute as one of the most distinguished lawyers in the domain. She started her career at a time when Indian IP laws and practices were undergoing substantial changes pursuant to India’s obligations to comply with the TRIPS agreement. Through the years, she has been consistently involved in the betterment of the country’s IP regime and has been engaged in advising Indian policymakers, implementers, and IP owners on global IP standards and enforcement systems. She is a true strategist and has led some of the most prominent and complex cases for large multinational and domestic corporations. She is identified by her clients as a seasoned and reliable counsel for the prosecution and enforcement of all forms of IP rights and planning and management of global patents, trademarks, and designs portfolios. She has also led numerous negotiation deals on behalf of her clients for both IP and non-IP litigation and dispute resolution. She has served as the leading counsel for a client base in over 138 countries in their IP management and litigation matters.

Manish Aryan, a managing associate at LexOrbis, is a lawyer licensed to practice as an advocate and a patent agent in India. Aryan holds a Bachelor of Technology (B.Tech.) degree in electronics and communications and a degree in law from IIT Kharagpur Law School. His experience includes appearing before various courts of law in India, including the High Court of Delhi, district courts in Delhi, and various other tribunals and adjudicatory bodies. Particularly in the field of intellectual property rights, his experience includes drafting, filing, and prosecuting patents (IPO, EPO, USPTO) for various multinational companies. He has appeared before various controllers and examiners of the Indian patent offices and attended official hearings/ interviews in more than 700 patent matters.