Trademark, copyright and Dr. Seuss’s racism!

31 July 2021

When the estate of Dr. Seuss pulled six of the author’s books for children due to changing societal norms, some fans were outraged. Excel V. Dyquiangco looks into the accompanying trademark and copyright issues.

In March 2021 – March 2, the 117th anniversary of Theodor Seuss Geisel’s birth – the estate of Dr. Seuss recalled and stopped publication of some of his most controversial work, including And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (which the estate pulled for its outdated portrayals of Asian people) and If I Ran the Zoo (which poses similar problems with depictions of Asians, Africans and Arabs).

“Today, on Dr. Seuss’s birthday, Dr. Seuss Enterprises celebrates reading and also our mission of supporting all children and families with messages of hope, inspiration, inclusion, and friendship,” the organization said in a statement. “We are committed to action. To that end, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, working with a panel of experts, including educators, reviewed our catalog of titles and made the decision last year to cease publication and licensing of [several titles published between 1937 and 1976]. These books portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong. Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families.”

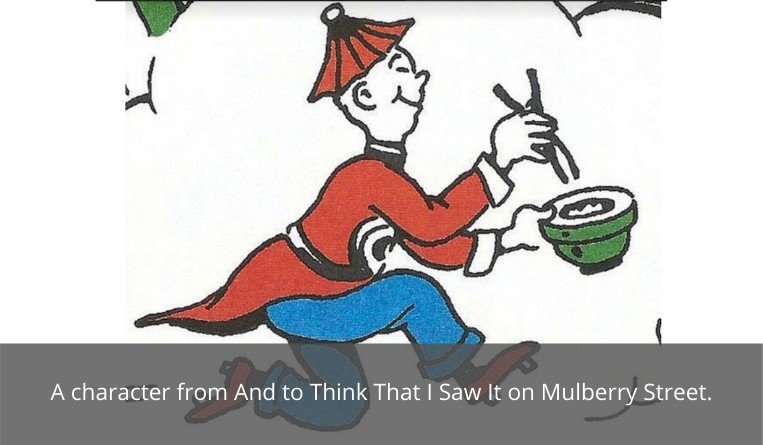

The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles issued a statement in support of the decision: “The Japanese American National Museum (JANM) welcomes the decision by the publisher of Dr. Seuss’ books to end publication of six of the author’s children’s titles that depict harmful caricatures of people of color, including Asian Americans and Blacks.

“One example is the stereotypical image in And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, of an Asian man with slanted lines as eyes, wearing a conical hat, and carrying a bowl with chopsticks.”

“The mainstreaming of racism and prejudice is deeply embedded in our culture. It is high time that Dr. Seuss’ work is examined,” Ann Burroughs, president and CEO of JANM, said in the statement. “The klieg light of history could not have provided more compelling evidence.”

Several months down the road, the questions on culture and morality continue. What happens to a work that was deemed non-obscene when it was published but is now considered obscene, considering that culture and the times have changed?

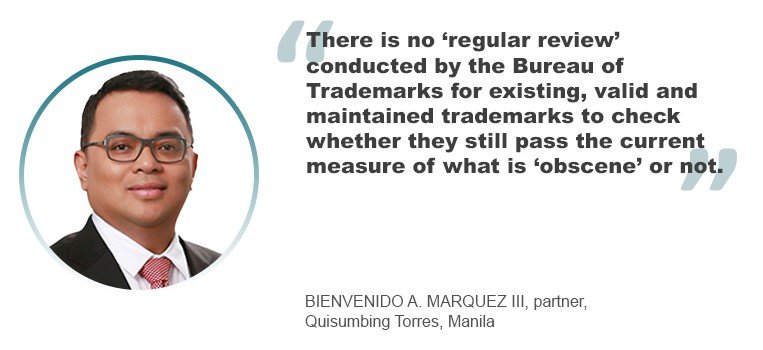

“If that happens to a trademarked item, in simple terms, nothing happens,” says Bienvenido A. Marquez III, a partner at Quisumbing Torres, the Baker McKenzie affiliate in Manila. “The determination of the propriety of a trademark (i.e., whether it is obscene or not) is made only at the time of the application. There is no ‘regular review’ conducted by the Bureau of Trademarks (BoT) for existing, valid and maintained trademarks to check whether they still pass the current measure of what is ‘obscene’ or not.”

He adds: “Technically, we believe that the BoT can invalidate the mark upon renewal (every 10 years for marks under the current IP Code, every 20 for marks under the Trademark Law) on the ground that it has become obscene, but to our knowledge, this has not been done. The BoT can institutionalize or issue specific regulations on what should be done for these types of marks.

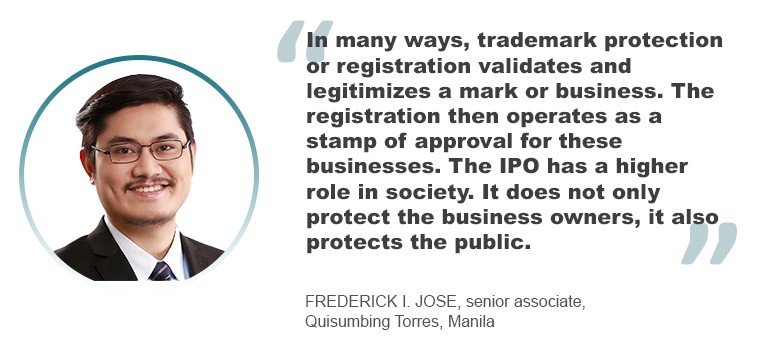

His colleague, Frederick I. Jose, a senior associate at Quisumbing Torres, adds that trademark protection should definitely be subject to decency, ethics and morals.

“In many ways, trademark protection or registration validates and legitimizes a mark or business,” he says. “Proprietors looking to have business deals with each other would necessarily check whether each others’ brands are registered. The registration then operates as a stamp of approval for these businesses. The IPO also has a higher role in society. It does not only protect the business owners, it also protects the public.”

Not of copyright?

Esther Wee, head of IP at Harry Elias Partnership in Singapore, says that when it comes to copyright, the issue of culture and copyright are two separate issues. They are not interrelated and should not be made so.

“The copyright regime provides a framework of control for the copyright owner and its estate (after the owner has passed on),” she says. “The owner should have the choice of whether to allow republication or reproduction of its work, especially when such an act would have an effect on the reputation of its creator.”

She adds that culture reflects the common meanings of a society.

“Culture and what is morally acceptable can change over time,” she says. “The applicable law therefore cannot follow the whimsical changes of culture which are essentially public opinion that can differ from country to country. The legal framework needs to be consistent so as to provide certainty to those relying on it to protect their rights in the long run.”

According to Michael Williams, a partner and head of the IP group at Gilbert + Tobin in Sydney, it is hard to dispute that the books come from a different era.

“While not everything old can be acceptable now, there is no bright line,” he says. “Copyright is a creation of a culture of giving creators a livelihood, rather than relying on patronage, by allowing them to retain control. That brings with it the right not to publish for many types of works, even if their reasons for doing so are unpopular. It is ironic that the decision to withdraw the tests, which is only possible by exercising copyright, is the more popular decision. Of course, copyright does not provide control over copies that are already in libraries – so you are safe to find a copy there.”

He then poses a question: Is this standard really good enough in a digital age, when libraries have instituted restrictions on access to materials due to Covid-19?

“We increasingly rely on digital copies and this is where the power of copyright to ensure no further dissemination is problematic,” he says. “There is an argument that if paper copies of the works are still available in libraries that digital copies should still be offered for loan.”

For Subhash Bhutoria, partner-designate at L&L Partners in New Delhi and founder of the Art Law India blog, copyright protects personal creativity, independent of cultural changes. “Therefore, while copyright laws would continue to protect the work which has not come into the public domain, it may not compel the use and exploitation of such protection, which is against social or public order in the present times,” he says.

Copyright and moral issues

“Traditionally, copyright has taken an agnostic position on the precise content of a work, so long as it meets the minimum criteria for protection,” says Williams. “There is no morality criterion under most copyright laws and copyright has been asserted over what in the past was regarded as immoral. In the few cases where a morality objection has been taken, it has usually been unsuccessful. A case we ran in the Federal Court of Australia in 2005-2006 and successfully defended the decision on appeal, an obscenity objection to video content – raised by alleged infringers – was rejected unanimously by the court.”

He adds that copyright usually leaves issues such as morality and decency to other forms of legal regulation.

“Freedom of expression may have a role in moderating the rights under copyright but not others, such as Australia,” he says. “And it is very difficult to know how such a defence to copyright infringement would work in practice.”

Bhutoria adds: “It is the Constitution (at least in the Indian context) which balances the expression with reasonable restriction. The copyright act promotes creative expression, which may or may not stand the test of reasonable restrictions, to freedom of speech and expression. The issues relating to morality, decency or public order are treated as criminal offences, and copyright law does not have much relevance except for the purpose of ownership.”