The Case of the Trademarks Registry and the Abandoned Trademarks

19 May 2016

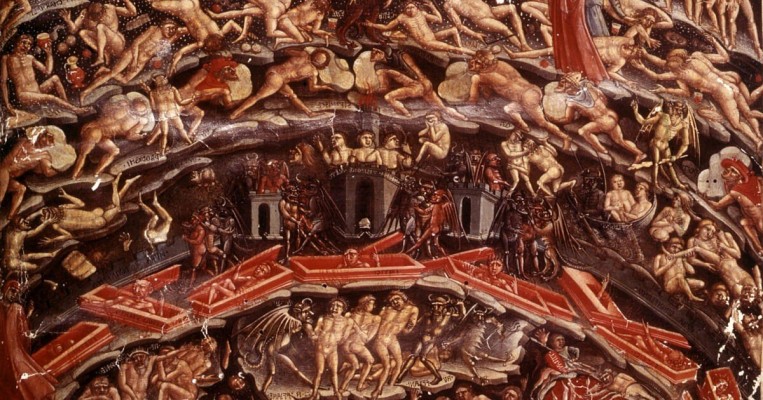

In the epic poem Dante’s Inferno, Dante passes through the gates of Hell, which is inscribed Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate. This translates to “abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” For a period in 2016, thousands of trademark applicants felt similarly of the Indian Trade Marks Registry.

These trademark applicants were shocked to discover around March and April 2016 that their trademark applications had been deemed abandoned by the Indian Trade Mark Registry. The shock expressed by these applicants was genuine and justified. Under Rule 38 of the Trade Marks Rule, 2002 the following procedure has been prescribed for the examination of a trademark application:

38: Expedited Examination, Objection to Acceptance, Hearing …

(4) If, on consideration of an application for registration of a trade mark or on an application for an expedited examination of an application referred to in sub-rule (1) and any evidence of use or of distinctiveness or of any other matter which the applicant may or may be required to furnish, the Registrar has any objection to the acceptance of the application or proposes to accept it subject to such conditions, amendments, modifications or limitations as he may think right to impose under sub-section (4) of section 18, the Registrar shall communicate such objection or proposal in writing to the applicant.

(5) If within one month from the date of communication mentioned in sub-rule (4), the applicant fails to comply with any such proposal or fails to submit his comments regarding any objection or proposal to the Registrar or apply for a hearing or fails to attend the hearing, the application shall be deemed to have been abandoned.” (emphasis added)

Relying on these rules, the Trade Marks Registry routinely issued objections to these trademark applicants at the stage of examination. When no response was forthcoming, the Trade Marks Registry issued the same applicants a notice deeming the mark as abandoned. The logical question, then, is why was there any shock expressed by the applicants after they failed to respond within the timelines stipulated by the Trade Marks Rules? The answer: The Trade Marks Registry’s notifications were never received by the applicants. The Trade Marks Registry uploaded its objections to the trademark application well as the subsequent notification of abandonment on its website; at no point of time did the Trade Marks Registry communicate its actions to the applicants.

To make matters worse, the notifications deeming trademark applications as abandoned appear to have been issued en masse. From information publicly available on the Trade Marks Registry website, 7,553 trademark applications were deemed abandoned in the months of January and February 2016 after examination by the 29 examiners working in the various offices of the Trade Marks Registry across the country. This data can be contrasted with the fact that the same 29 examiners deemed 166,767 trademark applications as abandoned in the month of March 2016 alone!

To remedy this situation, various applicants and interested associations filed writ petitions before the High Court of Delhi in April 2016. Just as in Dante’s Inferno, almost poetically, the happy ending for the aggrieved trademark applicants arrived close to Easter Sunday. The lead petition, Tata Steel v. Union of India, WP (C) 3043 of 2016, was heard on April 5, 2016, by Justice Manmohan of the High Court of Delhi. Observing that the figures of orders of abandonment in a short period of time were “startling,” the High Court of Delhi issued an order staying the Trade Marks Registry’s orders of abandonment. Additionally, the Court instructed the Union of India and the Trade Marks Registry not to treat “any trade mark applications as abandoned without proper notice” being served to any party affected by such order.

Around the same time, the Trade Marks Registry also issued a public notice in which, referring to the numerous complaints received on the issue of abandonment of the applications, the Trade Marks Registry, “in the interests of justice … decided to provide an opportunity to the applicants or their authorised agents concerned” to respond to the examination reports issued.

Thus, as it currently stands, trademark applications affected by these notifications of the Indian Trade Marks Registry have been revived and are available for the necessary action to be taken by the applicants. The Trade Marks Registry’s decision to abandon these trademarks on this scale remains largely inexplicable, with some insiders attributing it to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s mounting pressure on the Trade Marks Registry to clear its backlog for applications filed under the Madrid Protocol. Whatever the reason may have been, the judiciary’s quick steps to reverse the problems caused by the Trade Marks Registry and the Trade Marks Registry’s decision to correct its own error is heartening and has restored the faith of applicants in the trademark registration process in India.