NZ trademark suit highlights issue of discrepancy between colour swatch and written description

21 January 2021

A trademark suit involving the use of colour between Energy Beverages and Frucor Suntory New Zealand came to an end in December when the High Court ruled in favor of Frucor.

The case revolved around how a trademark registration should be interpreted if the written description and the colour swatch attached to the registration don’t match.

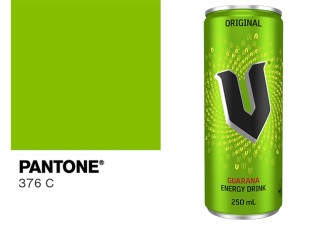

Energy Beverages which owns Mother energy drink, filed the lawsuit against Frucor, makers of V beverage, for the colour green in its bottles, packaging and advertising materials. Energy Beverages’s Mother Kicked Apple drink comes in a can bearing a similar colour. The company sought to invalidate Frucor’s trademark for the said colour which corresponded to Pantone 376c.

In May 2020, the Intellectual Property of New Zealand (IPONZ) rejected these attempts by Energy Beverages. In November, the company appealed this decision to the High Court in Wellington and last month, Justice Robert Dobson said he agreed with IPONZ’s decision.

The Court ruled that the written description should be favoured over the graphical representation.

The lawyers argued that the colour swatch attached to Frucor’s trademark application did not correspond to Pantone 376c. The former is a darker shade of green. IPONZ’s digitization of the colour swatch caused this alteration. As such, it did not match the green shade used in V’s packaging and advertising materials which is Pantone 376c.

They argued that the registration should thus be removed for non-use as Frucor had been using a different shade of green.

“Colour registrations in New Zealand are described in two ways. The owner is required to describe the colour in words, by reference to the Pantone shade. They are also required to attach a colour swatch showing the colour to the application,” said Laura Carter, a barrister at Sangro Chambers in Auckland.

“The question around whether the wording of the description or the colour swatch itself represented the trademark was a very interesting one. It seems like this point may have been the one that Energy Beverages got the closest to succeeding on,” Carter said. “Energy Beverages made the argument that normal people are meant to be able to search the register and understand what brands are available for them to use. On this argument, the fact it was not Frucor’s fault that the colour swatch did not show the correct colour was less important, and it was the normal member of the public’s understanding of the trademark that was registered that mattered, and they were likely to put more store in the colour swatch, or at least be confused about what was registered if they did look up the Pantone. But ultimately, the Court was reluctant to find that Frucor should suffer due to IPONZ’s digitisation of the colour swatch – especially as the judge considered that the issue could be resolved by simply correcting the register.”

Energy Beverages lawyers also argued that the Frucor trademark application’s written description lacked clarity. The latter trademarked Pantone 376c when used as the predominant colour in V’s packaging including its bottles and advertising paraphernalia. The lawyers said that Frucor did not state a definitive description for “predominant.”

“The Court found that as it was common practice to use this ‘predominant’ language in NZ specifications, it wasn’t unclear, particularly in a case like this where it’s just one colour that’s being registered,” said Carter. “If the trademark registration was for a combination of colours in a particular layout, the position might be different.”

Carter added that the most interesting issue from the perspective of trademark nerds may be Energy Beverages’s argument that the mark could be invalidated despite the fact it has been on the register for more than seven years. Frucor has owned the colour trademark since 2008.

“Under NZ law, once a mark has been registered for more than seven years, the grounds on which it can be declared invalid are markedly curtailed. This was a statutory interpretation argument based on whether the trademark even met the threshold of being a trademark. If it had succeeded, it would have dramatically changed our understanding of the operation of the law, and some trademark owners may be thankful that it did not succeed,” Carter said.

Espie Angelica A. de Leon