Since there are as many female experts on patents as there are male experts, there should also be as many women as there are men making up a panel of speakers or resource persons in the conference or forum,” Barredo said.

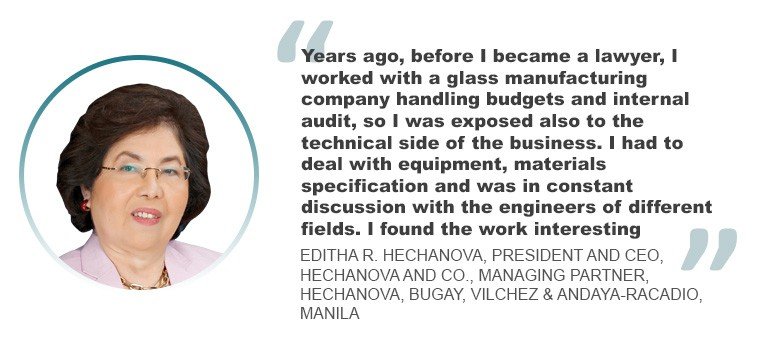

“The Philippines does not have a patent attorneysystem, and the programmes of the Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines are more directed towards qualifying and accrediting patent agents,” said Hechanova.

She shared that the association she helped to form, the Association of PAQE Professionals, Inc. (APP), conducts an IP masterclass program sponsored by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development of the Department of Science and Technology. The program covers patent drafting and commercialization of inventions. So far, APP has trained about 300 faculty researchers from state universities and R&D institutes.

What’s interesting is that women participants outnumber the men. “It becomes then desirable for the Philippines to generate more inventions or innovations in the future for the patent practice to become more attractive to both men and women,” claimed Hechanova.

Women lawyers should also be given as much opportunity to advance their career in patent practice. “I think women continue to be underrepresented in leadership, executive and entrepreneurial positions,” said Barredo.

However, for Barredo, something else needs to be addressed as well: the perception about women

lawyers in the workplace. “Having more women patent lawyers is definitelya good start, but it cannot stop there. Sexism and misogyny in the way women lawyers are perceived and treated must also be addressed for there to be true progress in terms of gender equality,” Barredo said.

Indeed, these women are proving the detractors wrong in their belief that members of the fairer sex are neither technical nor tough enough to handle patents and litigation.

“Even after spending over 27 years in the profession, patent practice still fascinates me as it gives me the opportunity to go through path-breaking inventions and connects me with the world of inventors and scientists,” said Mehta-Dutt.

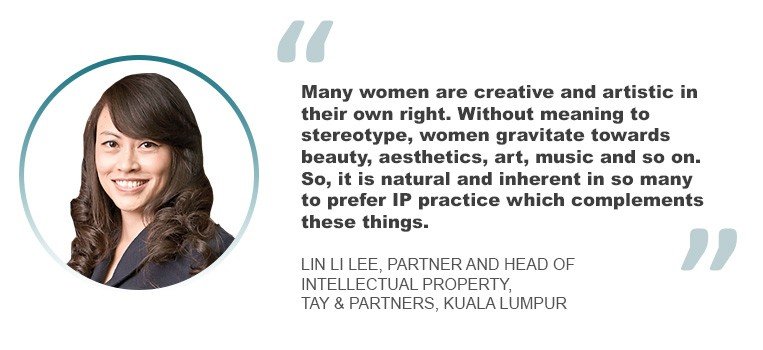

“Invention is not a bore once you’ve wrapped your head around it. The intricacies of the law and its application to the technical operation of the product or process also gets the creative juice flowing,” said Lee.

“So it is not just art that makes you dance.” And yes, these women are not just doing their job in brilliant fashion. They’re also having a ball while doing it.

Espie Angelica A. de Leon