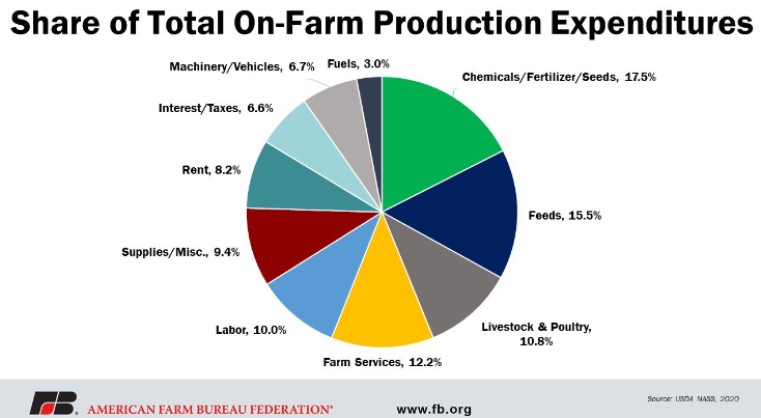

Investing in agrochemicals is a major expense for farmers, with the largest expected increase in production expense in 2022 being fertilizer, significantly impacting their crop production costs. This investment varies based on the type of chemicals, application scale and geographical location. While farmers often experience immediate benefits such as higher yields and reduced crop losses, long-term financial sustainability is jeopardized by challenges like pest and weed resistance. This resistance may need the use of larger doses or newer, more expensive chemicals.

Off-patent agrochemicals are significantly cheaper than their patented counterparts, increasing their availability in the market. Smallholder farmers, who often struggle with limited resources, benefit greatly from these lower costs and increased availability; it also enables farmers to adopt better pest and disease management practices. By protecting crops from pests and diseases, agrochemicals play a pivotal role in ensuring food security. This is particularly crucial in regions where food scarcity is a pressing issue, and the loss of a single harvest directly affects the local population.

Post-expired patents increase market competition as more companies can produce similar products, leading to lower prices and more choices for consumers. This heightened competition forces companies to innovate and improve their offerings to maintain market share, creating a dynamic and competitive market environment.

How does patent protect innovation of the farm?

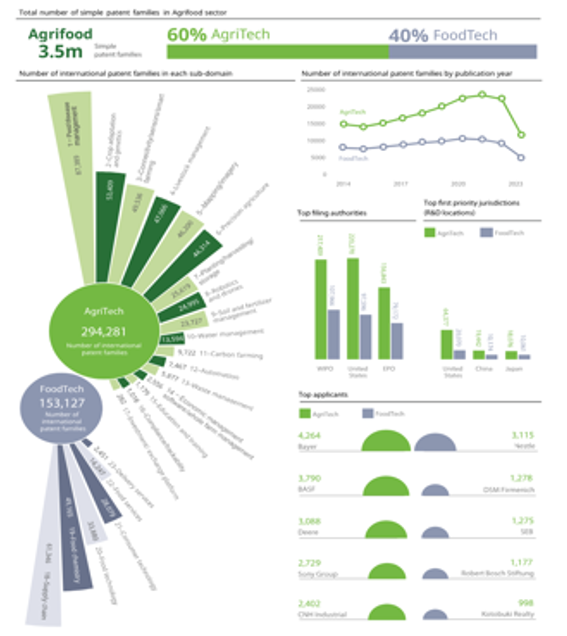

Patents play a critical role in fostering innovation, especially in agriculture. They provide the incentive companies need to invest in research and development, driving advancements essential for sustainability. This is particularly clear in the rise of biostimulants, biologicals and precision agriculture technologies – many of which are protected by patents – showing how intellectual property protection directly supports the development of sustainable agricultural practices.

“Patents incentivize companies to continue to invest heavily in research and development,” said DiMaio. “As a result, we’ve seen tremendous growth in areas that directly impact sustainability.”

Agrochemicals typically fall under the category of utility patents, and these patents generally expire 20 years after the filing dates of the relevant same or related patents, but some protection may remain in force.

In recent years, intellectual property offices have recognized that agrochemical active ingredient inventions cannot be exploited commercially until regulatory approval has been obtained and that this can be a lengthy process. This regulatory delay underscores the importance of patents in providing a window of exclusivity for innovators.

“Patents provide a vital incentive as they block competitors from using the innovator’s claimed technology without having to endure the costly resources of development. For small agrochemical businesses or startups, the entire company’s value may depend on the strength of its patents since without significant patent protection; larger companies can simply copy the products of a smaller competitor without recourse,” explained Jackman.

However, patents will eventually expire. Once a company’s patent on an agrochemical expires, competitors can begin producing similar products using the same formulas or ingredients. To stay ahead, companies often develop new formulations, enhanced versions or added components. While these may not offer the same broad protection as the original patent, they can still prevent competitors from accessing the most effective version of the product.

“Competitors will be limited to using older recipes that may not have all the same benefits as the new recipe,” said Nathaniel W. Lucek, a partner at Hodgson Russ in Buffalo who leads the firm’s IP&T practice. This means that even as patents on active ingredients expire, competitors entering the market may still face legal obstacles related to these auxiliary patents.

It is also a common misconception that a patent provides the owner with the affirmative right to practice the claimed invention. Patents are exclusionary rights. “The patent owner can only exclude third parties from making, using, selling or importing the invention,” said Jackman.

“So agrochemical companies need to be keenly aware of third-party patents and invest in strategies for having freedom-to-operate, such as design-around and invalidity strategies for non-expired patents. There are certain patent office invalidity challenges, such as European Patent Office (EPO) oppositions and U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) post-grant reviews, which must be filed within nine months from grant. Therefore, agrochemical companies need to constantly monitor for competitor patents and patent publications or risk missing key challenge windows,” explained Jackman.

Additionally, original patent holders often safeguard their innovations not only through patents but also by relying on trade secrets. Unlike patents, which require public disclosure of the invention, trade secrets allow companies to keep their innovations confidential, safeguarding the algorithms powering precision farming to the genetic makeup of bioengineered crops. This poses a challenge for generic producers, as they must replicate the quality and effectiveness of the original product without access to proprietary information not disclosed in the patent. Without these key details, generic manufacturers are forced to undertake costly and time-intensive research and development efforts to match the original agrochemical’s performance, which can significantly delay their market entry.

Special forms of intellectual property have been developed to extend the protection of a patented active ingredient after the expiry of the patent. “Most notably, member states of the EU offer supplementary protection certificates (SPCs), which extend the patent term for European patents directed to medicinal and plant protection products which have been the subject of pre-marketing regulatory approval. SPCs can extend the patent term by up to five years,” said DiMaio.However, the U.S. does not offer patent term extensions for agrochemicals, but there are frameworks available in other countries for patent term extensions for agrochemicals.

Despite these mechanisms, the agrochemical industry still faces some challenges that go beyond patent protection. “In fact, the main challenges they face lie more in the uncertainty of the legal and policy environment, the challenges of technological innovation, market competition pressures and limitations on funding and resources,” said Tai. She added that changes in laws and policies can affect how seed companies and breeders operate, particularly in areas like intellectual property rights and biodiversity regulations. To succeed, independent seed companies and breeders must navigate this uncertainty while also promoting biodiversity and innovating to stay competitive in the market.

Data harvesting

In the sun-drenched fields of modern agriculture, drones, sensors and satellites monitor the way crops grow. Precision agriculture tools gather a treasure of data and paint a detailed picture of crop health, soil conditions and weather patterns.

The rise of AI in agriculture, encompassing precision farming, predictive models, farm management platforms and AI-powered drones, is revolutionizing the industry. These advanced tools are designed to boost productivity and sustainability, providing farmers with unprecedented insights into their operations. However, as these technologies collect vast amounts of data, concerns are growing about the ambiguity of agreements and legal frameworks surrounding data collection, processing and sharing. This uncertainty can lead to significant challenges in data privacy practices.