How can Schedule A litigation combat online counterfeiting and infringement? Cathy Li discusses its mechanism, challenges faced by defendants, ethical concerns and its broader implications for global IP protection and cross-border commerce.

Sealed files stack high on the desk of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, each a catalyst in the battle against intellectual property theft. Behind their labels lies a relentless game of strategy thriving in the shadows of ecommerce.

In these cases, identities are rarely straightforward. Defendants, cloaked in aliases and scattered across the internet, are listed collectively in Schedule A. Plaintiffs, just as cautious, often file entire complaints under seal, seeking to outmaneuver counterfeiters poised to dismantle and rebuild their operations at a moment’s notice.

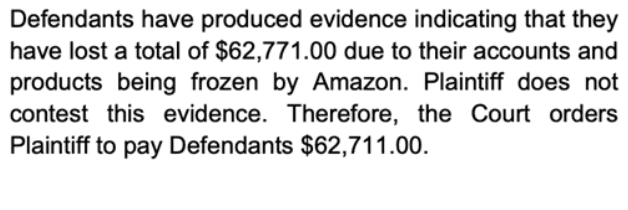

Each file opened sets the stage for swift action. If defendants do not appear, the plaintiff obtains a final judgment for US$150,000, disgorgement of frozen funds and the closure of accounts, according to Baruch S. Gottesman, the U.S. counsel representing the defendants in the Zhaoyou Chen v. Partnerships and Unincorporated Associations Identified on Schedule A case. Temporary restraining orders (TROs) can instantly shut down online storefronts. It’s a judicial tightrope walk where every ruling echoes across the battlefield of global ecommerce.

Many defendants remain unaware of lawsuits against them until judges issue TROs that freeze their U.S. bank accounts and shut down their online stores. At this point, defendants often find themselves with no choice but to agree to undisclosed settlements.

The complaint does not identify specific wrongdoings or name any individual defendants. Instead, it claims ownership of copyrights, trademarks or patents and includes a list – a “Schedule” – that identifies dozens or even hundreds of defendants who sell products online.

“As defendants, sellers often operate independently, compete with each other, without any collaboration. Plaintiffs always improperly group them based solely on selling similar items, failing to show a direct connection between the defendants’ activities,” said Barclay Jiang, a partner at Beijing Qinghui Law Firm and Tsingyuan Hui IP Agency in Beijing and a patent attorney in both New York and Beijing.

As these techniques protect intellectual property, they are potentially becoming a way to seek profit. The nature of Schedule A cases, which can be served through email and give defendants less than a month to appear, presents challenges to defendants.

“We have many links, and due to this issue with one link, their lawyer applied to freeze all links in our store, freezing the entire store,” said a Chinese Amazon seller, expressing one of their frustrations to Asia IP over the legal actions taken against their store. They received a TRO, followed by a preliminary injunction (PI). The seller emphasized that freezing a single link should not lead to the entire account being frozen, as it causes significant operational losses.

Despite resolving issues, sellers worry about Amazon’s new policy on repeated account health violations. Introduced in October 2024, this policy could lead to account suspension or closure if a seller repeatedly violates the same policy within 180 days.

“From Amazon’s perspective, they want to better control sellers and reduce the frequency of performance issues and violations. However, from our perspective, we do not frequently violate rules. But we are concerned that if we step on a landmine again, the performance issue from the first case has not been removed, it will count as a repeated violation,” the Chinese Amazon seller told Asia IP, highlighting that the fight is not over for them.

Rules of Schedule A

Schedule A litigation, now widely used in the Northern District of Illinois, has emerged as a critical legal mechanism for intellectual property owners to combat online counterfeiting and infringement. The cases are filed under seal, allowing plaintiffs to secure TROs that freeze Amazon Standard Identification Numbers (ASINs) and associated funds without notifying defendants in advance. This secrecy ensures that alleged infringers cannot relocate assets or modify listings, giving plaintiffs a strategic advantage.

According to Santa Clara University law professor Eric Goldman and Chicago-Kent College of Law professor Sarah Burstein, the strategy reveals a sophisticated yet underreported system of mass-defendant intellectual property litigation known as the Schedule A Defendants Scheme (SAD Scheme).

Predominantly occurring in the Northern District of Illinois, this “scheme” primarily targets online merchants based in China. The SAD Scheme exploits vulnerabilities in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, judicial deference to IP rights owners and the liability exposure of online marketplaces.

“Most judges allow hundreds of unrelated defendants in a single lawsuit, and almost all judges decide motions on the papers and allow virtual appearances,” said Gottesman.

The Northern District of Illinois is a preferred venue for Schedule A litigation due to its specialized expertise in managing complex ecommerce cases. Judges in this district have established a reputation for consistent and efficient rulings, making it an attractive jurisdiction for intellectual property enforcement. The quick adjudication of these cases further solidifies its standing as a hub for addressing widespread online infringement.

The Schedule A filing system capitalizes on modern interpretations of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure that have come to recognize the difficulty in finding or serving parties outside of the United States.

Eunice Yan, a senior partner at Zhiheng Law Firm in Shenzhen and a local counsel advising some of the defendants in the Zhaoyou Chen v. Partnerships and Unincorporated Associations Identified on Schedule A case, told Asia IP: “The defendants need to engage with these cases. The defendants need counsel in the United States to fight these cases.” She expressed that this is another challenge Chinese defendants may need to overcome.

The defendants faces multiple obstacles. In Case No. 1:24-cv-07164, some are claiming there is no infringement, while others are seeking an answer from the plaintiff but have not received a proper response to resolve the matter. Legal tactics in Schedule A cases also highlight some ethical concerns. In cases involving patents, for example, defendants often face accusations of infringement based on designs that bear minor similarities to the plaintiff’s product.

“The plaintiff compared each of the defendant’s patent pictures one by one, and when it came to me, he claimed the connector of my tube has ribbed patterns just like his. His patent has a ribbed pattern on the exterior of the tube; however, ours did not, and he claimed ours did,” one of the defendants, Yu, told Asia IP, explaining that his adapter’s patterns also served different purposes.

“We sold this product around 2019; he registered his patent in 2020, and in 2021, it was approved. We also have not seen this product on the market at the time,” Yu added. He pointed out that the plaintiff’s patent and his own demonstrated similar products, but the specific designs served different purposes, arguing that it does not constitute infringement. Yu also claimed to have never seen the plaintiff’s product on the market when his product was sold in 2019.

In the realm of intellectual property, there are instances where legal experts exploit gaps in the system to their advantage. For example, in the United States, there is a one-year grace period for patent applications. This means that after a product is publicly disclosed, the inventor has one year to file for a patent. However, if the original inventor fails to apply within this period, others can potentially file for the patent themselves, capitalizing on the inventor’s oversight.

This situation often arises when a product is already on the market but has not been patented by its creator. Observing the product’s success, another party might step in and file a patent application, effectively claiming the rights to the invention. This practice, while legally permissible, raises ethical questions about the exploitation of the grace period.

In the United States, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) allows a one-year grace period from the earliest date of public disclosure to file a patent application. This grace period applies to both utility and design patents and is available only for the inventor’s own prior public disclosures, not for those made by others.

Tactics using Schedule A litigation blurs the line between strategic exploitation of legal provisions and outright bad faith. Critics argue that such practices undermine the spirit of intellectual property laws, which aim to reward true innovation rather than opportunistic maneuvering.

In the context of Schedule A litigation, these legal grey areas are often amplified. Defendants like Yu, for example, face significant hurdles in proving non-infringement when the plaintiff’s claims hinge on seemingly minor design similarities. Yu’s assertion that his product predates the plaintiff’s patent application highlights a broader issue: the potential for abuse of the grace period by parties seeking to weaponize intellectual property laws against legitimate competitors.

Adding to the complexity, defendants in these cases often lack the resources or expertise to navigate the intricacies of U.S. patent law, particularly when faced with procedural advantages such as sealed filings and TROs. As Yan pointed out, Chinese defendants must overcome not only legal challenges but also logistical barriers, including the need to retain U.S.-based counsel and contend with unfamiliar legal norms.

Defendants strike back